IO – The Government and a host of research institutions have forecasted strong economic growth for Indonesia in 2022. The GDP target set forth the state budget (APBN) is 5%-5.5%, while Bank Indonesia came up with a 5.5% projection. However, the emergence of more virulent, vaccine-resistant new Covid-19 variant called Omicron has become a serious threat to economic recovery prospects. Even if it is under control, the economy will still face several other pressures, on the fiscal and monetary side, as well as inflation.

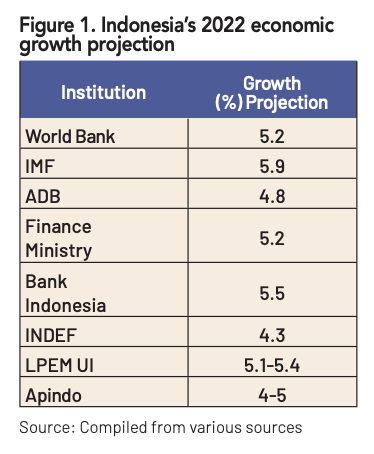

The World Bank predicts Indonesia’s economy can grow 5.2% in 2022, slightly higher than the 4.8% from the Asian Development Bank (ADB). Meanwhile, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its October 2021 World Economic Outlook came up with 5.9%. This, however, is lower its projections for neighboring countries Vietnam, the Philippines and

Malaysia, expected to grow 6.6%, 6.3% and 6%, respectively.

Optimism about Indonesia’s economic recovery and growth is also mirrored by the analysis of national research institutes and trade associations: 4.3% from the Institute for Development of Economics and Finance (INDEF), 5.1%–5.4% from the University of Indonesia’s Institute of Economic and Social Research (LPEM UI), and 4%-5% from the Indonesian Employers Association (Apindo). Every one of them agree that Indonesia’s economic performance in 2022 will surpass the estimated 3% GDP growth in 2021. (FIGURE-1)

Four hurdles

The bubbling optimism, however, needs to be tempered by a dose of caution. Omicron, fiscal burden, monetary pressure and the threat of inflation have further complicated the economic outlook. The unpredictability of the pandemic is probably the greatest concern of all. Already, an Omicron outbreak around the world, especially in worst-hit Europe, have forced European countries to reimpose lockdowns, such as in Rotterdam and London during Christmas.

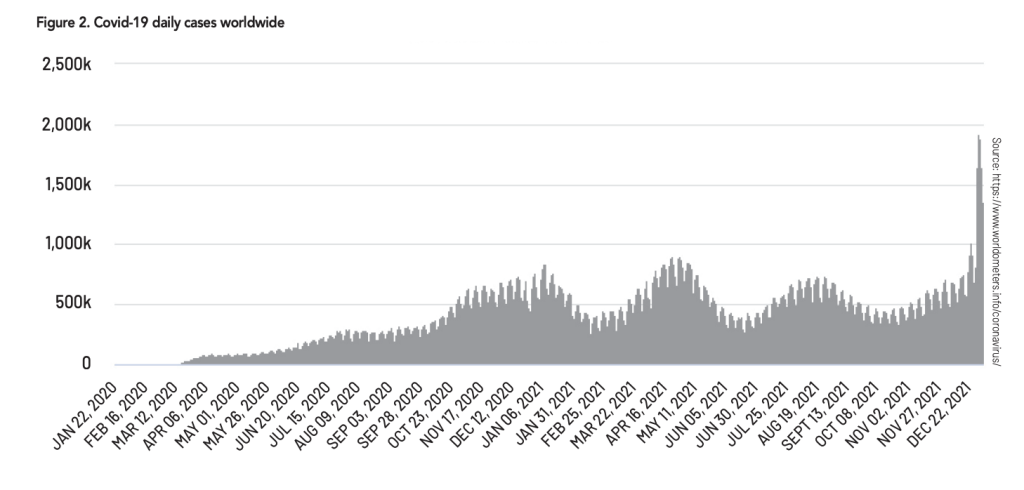

Globally, Omicron has raised the specter of a fourth wave of the pandemic. The variant, first detected in Botswana and South Africa on November 24, 2021, has caused Covid-19 daily cases to surge. As of December 30, 2021, the global tally has touched 1.8 million cases, the highest since the initial outbreak in Wuhan, China, at the end of 2019. This brings the cumulative caseload worldwide to 290 million as of the end of 2021. (FIGURE-2)

Known as a “super mutant”, Omicron has the most mutations compared to other variants, and it is at least 4.2 more infectious than Delta. This raises concerns about a large-scale community transmission which could lead to the collapse of the healthcare system. At the same time, Covid-19 vaccine uptake, especially in Indonesia, is still far from the target.

As of January 1, 2022, of the 208 million vaccine recipients, only 114 million (54%) of Indonesians have been double-jabbed, with 161 million (77%) having received their first shot. So far, only 1.2 million people have had their third dose (booster). With this achievement, we should be worried about a third wave of pandemic in Indonesia.

This fear becomes even more pronounced considering that since January 3, 2022, many regions in Indonesia have reverted to face-to-face classes (PTM), such as in Jakarta. In addition, the cancellation of public activity restrictions enforcement (PPKM) level 3 during the Christmas and New Year festive season led to heightened worry that Omicron-fueled third wave may strike by end of January. If this prediction becomes reality, the national economic recovery agenda will be at risk.

The second hurdle is the fiscal burden. 2022 is the last year where state budget deficit in excess of 3% of GDP is allowed under Government Regulation in Lieu of Law (Perppu) 1/2020 on state financial policy and financial system stability which has been then signed into Law 2/2020 on state financial policy and financial system stability to control a Covid-19 pandemic.

The state budget deficit threshold in 2022 was pegged at 4.85%, lower than 6.14% realization in 2020 and 5.82% outlook in 2021. If the deficit is to return to a maximum of 3% in 2023, there will be a heavy fiscal burden. The most obvious effect would be that the debt-to-GDP ratio will increase to around 37 percent, from 30.2% in 2019.

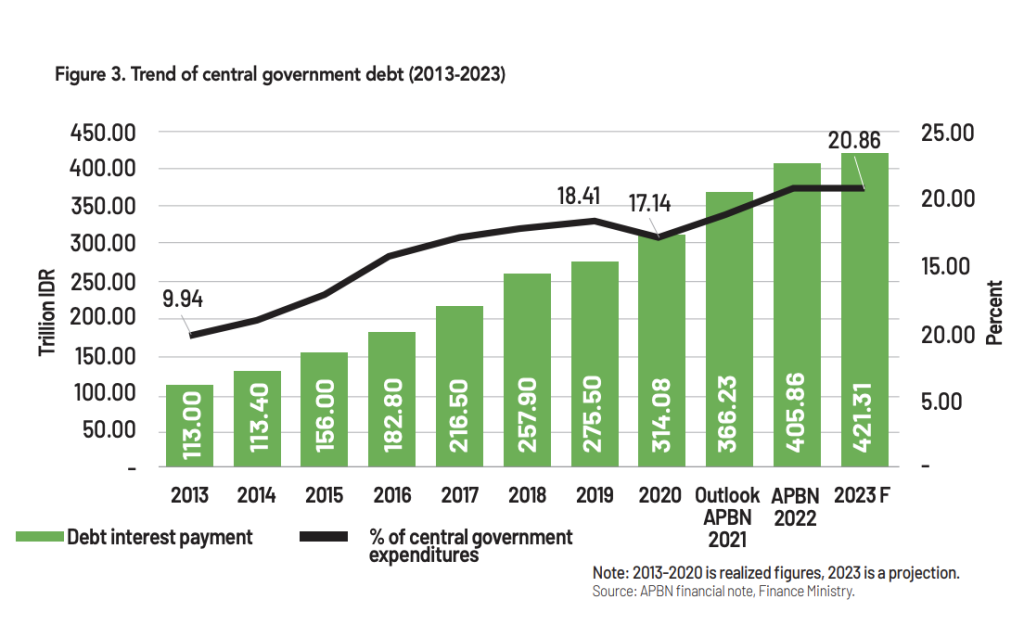

The increase in debt ratio will have an effect on the payment of interest expenses. In 2013, interest expense was 9.94% of total central government expenditures. This nearly doubled to 18.41% in 2019. In 2020, this dipped to 17.14%. (FIGURE-3)

Furthermore, the decline in the ratio of debt interest payments to central government expenditure in 2020 was due to an increase in central government expenditure to Rp1,832.9 trillion from Rp1,496.3 trillion in 2019. On the other hand, the Government’s interest expense expenditure in 2020 was Rp314.08 trillion, or Rp39 trillion more from Rp275.5 trillion in 2019. In Budget 2022, the Government has set the debt interest expense expenditure to Rp405.86 trillion, up by 20.87%. In 2023, the projection for debt interest payments is Rp421.3 trillion, with the assumption that central government expenditure is Rp2,019.7 trillion.

Covid-19 spending for the 2020 fiscal year has jacked up central government expenditure by Rp336.6 trillion, and this has an implication for debt interest expenses, post-2022, in that the Government must find new sources of income, which many economists predict would likely be problematical in 2023.

Monetary pressure

The next pressure on the Indonesian and the global economy is on the monetary sector triggered by the Fed’s monetary policy normalization. In 2022, the central bank of the US plans to reduce monetary stimulus (tapering) and increase its benchmark interest rate. This policy has the potential to trigger capital outflows from developing countries, including Indonesia. The reduction in monetary stimulus in the US is in line with the faster-than-expected economic recovery in the country.

The tapering could weaken of the Rupiah exchange rate against the US dollar. In 2021, the Rupiah weakened by 2.6 (the middle rate). On January 4, 2021,the Rupiah was traded at Rp13,903/US$; this weakened to Rp14,265/US$ by December 31, 2021. Despite a stronger position early in the year, it weakened in the middle of the year before strengthening again at the end of the year. The monetary authority needs to stay vigilant in 2022, given the volatility in the global monetary and financial sector due to plan by the US and European central banks to cut back on economic stimulus.

One of the policies that can be taken to reduce the impact is to increase the domestic benchmark interest rate. This policy will result in higher lending rates. If this happens, interest rates on loans will rise, leading to slower demand for consumption, capital and investment loans. Ultimately, economic growth will be adversely affected. (FIGURE-4)

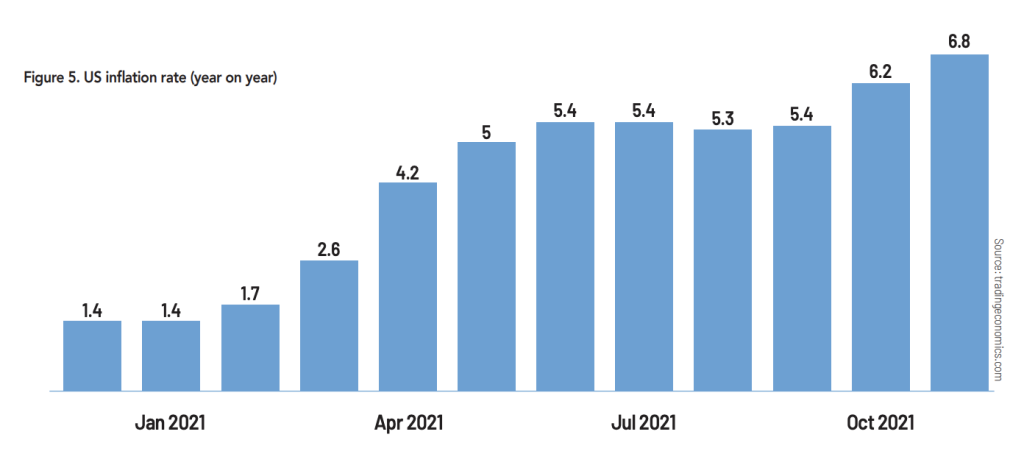

Looming high inflation in the US poses a threat to the global economy. In November 2021, the US annual inflation hit 6.8%, its highest since June 1982. This is way above the Fed’s inflation target for 2021, which was 2%. In addition to economic recovery, the spike in global commodity prices, pressure from rising wages, supply disruptions, and a low base effect were key factors that are driving inflation in the United States.

High inflation in the US can potentially trigger import inflation. Commodities imported from the United States include wheat, soybeans and machinery. These can push up food prices domestically, and consequently put pressure on the economy. (FIGURE-5)

This leads us to the next hurdle, inflation. Although inflation in 2021 was under control at below 2% (assuming inflation rate in December 2021 was below 0.3 percent), inflation in 2022 could reach 3%, according to government projection, as the national economic recovery continues its momentum.

Inflation in 2022 can simultaneously be driven by imported inflation, cost-push inflation and supply chain disruption. Import inflation is caused by the increase in global demand, which is predicted to increase further in the Spring, when the demand for goods and services surges faster than supply. This is because economic and social activities in the northern hemisphere tend to increase spring and summer, assuming that Omicron is under control. As a result, global demand for goods and services may increase, while supply of goods yet to fully recover.

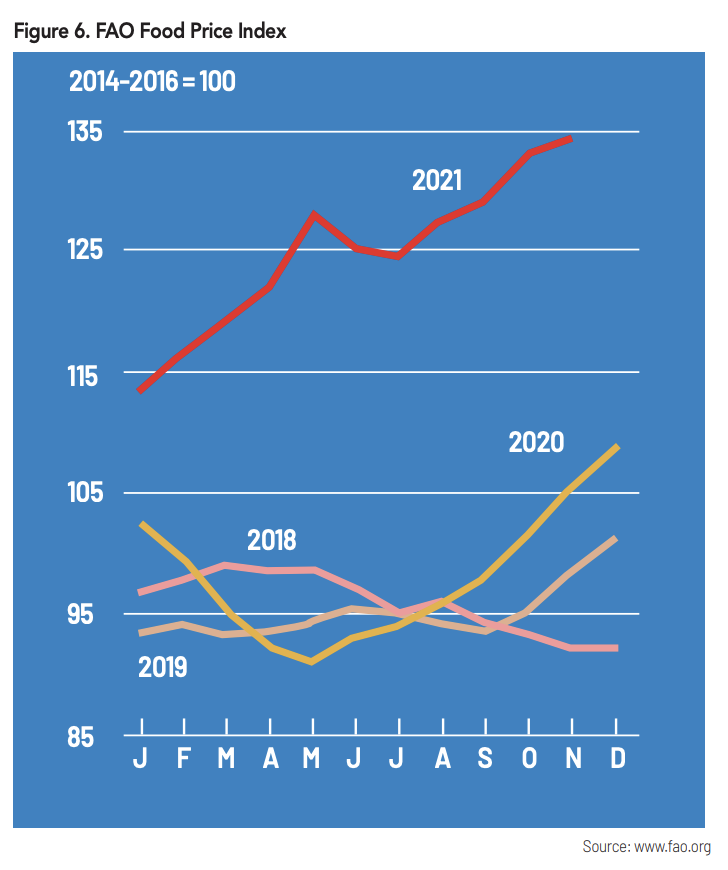

For Indonesia, this will primarily drive up the prices of imported food commodities. Data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) shows that the FAO Food Price Index (FFPI) in November 2021 was at 134.4, up 1.6 points (1.2%) month to month or 28.8 points (27.3%) year on year. This is the highest since June 2011. Prices of cereal and dairy products increased the most, followed by sugar. Meanwhile, meat and vegetable oils fell slightly from the previous month. (FIGURE-6)

Domestically, demand will be driven by economic recovery, as Covid-19 caseloads are kept under control, leading to social distancing restrictions in several regions, coupled with the increase in vaccination coverage which boosts consumer and business confidence.

The next source of inflation is supply side inflation, both cost-push inflation and the scarcity of goods due to a supply shortage. Cost-push inflation happens because of an increase in lending rates, following the hike of BI’s 7-day reverse repo (BI7DRR) rate. This in turn pushes up investment costs for manufacturers and service providers.

Additionally, there are several government policies in 2022 that can raise cost-push inflation, namely, the plan to increase the price of non-subsidized LPG, electricity tariffs for non-subsidized customers, the phasing out of fuel with a research octane number (RON) below 92, implementation of a new value-added tax (VAT) scheme, cigarette excise tax increase and the potential rise in premiums for the Health Care and Social Security Agency (BPJS Kesehatan).

The policy will fuel inflation, which in turn tends to erode purchasing power. Sectors that will be affected by non-subsidized LPG price hike include trade, hospitality and lodging, and food and beverages. Meanwhile, the fuel policy and plan to increase BPJS Kesehatan premiums can potentially trigger inflation in the transportation and healthcare sectors.

At the same time, the stimulus from the Government, through the National Economic Recovery (PEN) program, fell to Rp414.1 trillion in 2022, from Rp658.9 trillion in 2021. This may weaken consumption by household and the public sector and further undermine economic growth, as it accounts for 55% of GDP.

Making matters worse, supply shock can lead to a scarcity of goods. At a global level, this has happened where there is a container shortage, affecting imports and exports. The impact may not be immediately felt in 2021 as there is a time lag but it will carry over to 2022.

On the domestic side, disrupted food supply caused by la Niña has the potential to affect rice production. The peak of la Niña, which brings heavy rainfall, is predicted to occur in December 2021-January 2022, and can threaten the rice planting season for March 2022 harvest. If this happens, national rice production could be disrupted, leading to rice shortages as March/April is a main rice harvesting season.

The 2022 inflation target should be understood as topping the 3% rate. Learning from what happened in 2021, the imbalance created by supply and demand shock has caused the price of energy commodities to spike as well as pushing container shortages. This further increased the price of CPO, used for substitute fuel. Increase exports of one of Indonesia’s top export commodities eventually pushed up the price of cooking oil domestically.

Fiscal response

The Government has secured revenues in 2022 and beyond by increasing cigarette excise tax by 12% on average. The largest increase is imposed on Machine-made Kretek Cigarettes (SKM) type II B by 14.3% and Machined-made White Cigarettes (SPM) type II B by 14.4%. The Government projects that this can generate up to Rp193 trillion, accounting for almost 10% of state revenue. (FIGURE-7)

Other potential source of revenue comes from Bank Indonesia liquidity support (BLBI) receivables of Rp110 trillion. The President has issued a decree on the formation of a task force to collect state funds from BLBI obligors. The task force, whose mandate will expire in 2023, gives flexibility for the Government to optimize the collection of BLBI funds which can be used to beef up our 2022-23 Budget.

The Government might also offer a second tax amnesty in 2022. If we use the first edition of tax amnesty as a reference, the potential revenue will not exceed Rp150 trillion. Furthermore, the second tax amnesty stipulated in Law 7/2021 concerning the Harmonized Tax Law (HPP) has two different tariff schemes.

First, for individual and corporate taxpayers who participated in the first tax amnesty, a tax amnesty will be given for assets acquired up to December 31, 2015 and not reported in the previous tax amnesty. The final income tax rate for the first scheme is 11% for overseas assets that are not repatriated to the country, 8% for overseas assets repatriated and domestic assets and 6% for overseas assets repatriated and domestic assets invested in sovereign bonds (SBN) and downstreaming of natural resources.

Second, for individual taxpayers whose assets had not been reported in annual tax return (SPT) for tax year 2020 are offered a final income tax rate of 18% for overseas assets not repatriated, 14% for overseas assets repatriated and domestic assets, and 12% for repatriated overseas assets and domestic assets invested in sovereign bonds (SBN) and downstreaming of natural resources and renewable energy.

Furthermore, the Government has secured the expenditure side through the passage of Law on the fiscal relations between central government and regions (HKPD Law) which amended Law 33/2004 on center-regions fiscal balance. In the HKPD Law, there is one significant change, namely, the abolition of the clause on general purpose grants (DAU) of at least 26% of net domestic tax revenue (PDN) as stipulated in article 27(1).

The implication is that now the central government has the flexibility to transfer DAU to the regions without having to meet the mandatory 26% provision. As a result, the central government at least has the flexibility to manage fiscal risks in 2023.

Even though the fiscal policy for 2022 has adopted alternative policies that can boost state revenues, the Government needs to pay attention to its disbursement. One of the issues in national fiscal expenditure that still draw public criticism is the accumulation of budget absorption toward the second semester, especially in the regions, and the large amount of unspent funds (SiLPA). As seen in Budget 2022, the amount of SiLPA in 2020 reached Rp216.4 trillion. However, 2021 SiLPA is projected to be lower (Rp31.6 trillion as of November 2021).

Non-fiscal response

The Government has swiftly responded to the ongoing pandemic through various fiscal policies expected to increase revenue while reducing government expenditure. However, it also needs to focus its attention on non-fiscal policies, in response to inflation and the Fed’s interest rate hike.

The Government needs to anticipate rising prices caused by imported inflation as well as supply and demand shocks. It can start by identifying imported commodities that can cause imported inflation and come up with mitigation policies. Do not let the repeat of the increase in soybean prices in H1-2021, caused by a sharp increase in global demand from China, as well as other basic commodities that are still imported by Indonesia, such as beef, wheat, corn, and garlic. Mitigation can be done by pursuing long-term contracts (more than one year in length) to secure the supply of imported goods. Next, it can identify substitute goods that can be produced domestically.

Another measure is to map out regions vulnerable to rising prices of basic commodities. The main objective is to detect any supply-demand imbalance, if the Covid-19 pandemic subsides.

In response to the Fed’s tapering, the monetary authority must carefully monitor domestic liquidity, the financial sector and Rupiah exchange rate. Close synergy with the Finance Ministry and other stakeholders through the Financial System Stability Committee (KSSK) is paramount so that monetary, fiscal and real sector policies can be synchronized.

Last but not least is Covid-19 handling, especially to deal with new variants. This is important considering that once the pandemic wave strikes, it will have a profound impact on long-term economic growth and slow down national economic recovery in the short term. Hopefully in 2022 and beyond, Indonesia will no longer face another pandemic wave and will soon enter an endemic period.