IO – Marianne North was that most enviable of all creatures: a woman of independent means and because of this she was able to do what she loved most namely, to travel the world painting the wonderful and unique plants of different countries. She was able to create the ideal life as she combined the three great passions of her life: painting, travelling and plants.

In Kew Gardens stands the Marianne North Pavilion for which she provided the funds and which was designed under her supervision. The building has elements of a Greek temple and houses her botanical paintings. It was first opened in 1882. The interior is decorated with 246 types of wood collected during her travels and the gallery houses her botanical paintings. She was an extremely prolific painter and there are 832 of her paintings in oils in the gallery.

This was unusual for botanical paintings at the time, as most botanical illustrations were made in water colours, and not oils. Also, her paintings are not limited to specific plants but include the landscape where the plants grew as well as insects, birds and even at times, animals found in the vicinity. North was unusual in that she drew her plants in their natural habitat. By painting them in their natural settings she provides us with additional information about the ecological relationship of the plant to its environment. This additional information is useful to scientists now because at the time, usually all the information they would receive about the location of a botanical drawing was that it grew in India or China or Southeast Asia, for example. Now, when plants are scientifically collected their GPS locations are included. So, her paintings which display the plants with their environmental background also provided information about where and how those plants grew.

Not only botanical enthusiasts find North’s paintings exquisite but also the general public. She was a good artist with an eye for beauty. As a young woman she received training in using water colours and in the beginning painted using them but later she was introduced to oils and loved the intensity of colour that was possible with oils. In her handling of light North was influenced by the Impressionists and like them she enjoyed painting en plein air or outside in the open air. During her time, this was frowned upon as artists painted in studios. Should the reader find themselves at Kew Gardens then the little gallery is well-worth a visit. It is located south of Kew Garden’s Victoria Gate just across from the Temperate Green House – and if you go, do feel free to bring your camera to take photographs.

What brings her paintings into the news again 132 years after her death, is that a Chinese botanical illustrator by the name of Tianyi Yu, discovered a new plant species in one of her paintings in 2021. At the time, he was working at Kew Gardens while studying for a master’s degree. He has since returned to Beijing, where he now works as a freelance botanical illustrator and researcher.

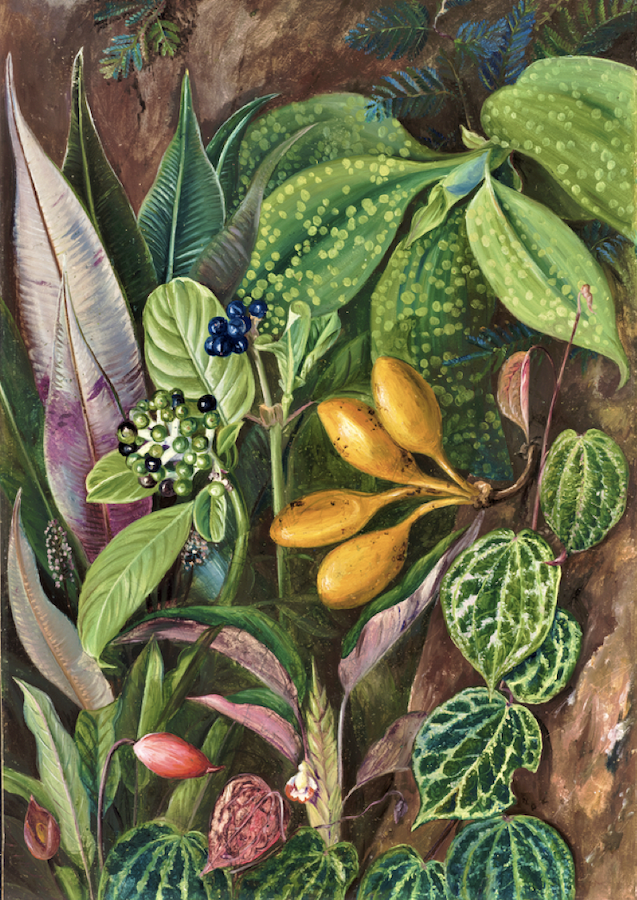

The new species of plant appears in a painting of Marianne North’s entitled ‘Curious Plants from the Forest of Matang, Sarawak, Borneo’ which she painted in 1876 while on a visit there. The painting consists of a group of plants gathered together and what drew Yu’s eye was a plant with green leaves and colourful berries. Some were still green, while others had turned black but a few were a deep blue colour. The descriptions of the plants in the painting were not very clear and no plant names were mentioned in the title of the painting. The plant with the blue berries had been described as Psychotria or wild coffee but Yu knew that the genus Psychotria does not have blue berries. He also knew that North was very careful with her plant paintings and did not take license in the drawing of plants and their habitat. In fact, she always carefully painted exactly what she saw.

After studying the plant, Yu decided that it was of the genus Chassalia. It is a poorly documented species growing in countries from Africa to Southeast Asia with few pictures of the genus available. Fortunately, Kew Gardens also has a herbarium with over seven million specimens and so, he was able to compare the plant in North’s painting with a specimen of Chassalia from the Matang Forest in Sarawak kept at Kew Gardens’ herbarium. Yu was able to locate a specimen of Chassalia collected in 1973 from the Matang Forest, in the Kew collection. The plant in the painting proved to be a newly identified species of Chassalia which Yu named Chassalia northiana. There are already four other specimens named after the remarkable Marianne North and it is inspiring that her legacy of botanical paintings continues to bring new information to scientists.

In the Atlas Obscura article by Gemma Tarlach about Yu and his discovery, he is quoted as saying, “It is still very hard to go to all the places she (Marianne North) visited, even in this day, and some places she visited still lack scientific survey. There are still many species in her paintings without information or a photo, or even a scientific name, so the paintings are still very important for scientific research.”

Marianne North was clearly an adventurer for during her life time she managed to visit over 15 countries and paint the flora there – often travelling into dense forests or up swift rivers or into the mountains in the interior accompanied by local guides. This was very unusual behavior for a 19th century European lady. She often held painting exhibitions of her work in England and there are more news reports from the period about her travels and her paintings than about male botanical explorers. This was in part because she was a woman and at that time it was highly unusual for women to travel alone especially to such remote areas. Being unmarried, socially well-connected and of ‘independent fortune’ is what made it possible for her to travel alone to exotic destinations, at the time.

In 1876, Marianne North visited Borneo or Sarawak to be precise, travelling from Singapore in the small weekly steamer with which she also travelled up a broad river to the capital, Kuching; a four-hour journey through flat country filled with coconut, nipah and areca palms, and mangrove swamps. Eventually, on the right hand side of the river appeared a flight of steps that lead up to the Rajah’s Palace. She sent her letter of introduction from the Governor of the Straits Settlement, Sir William Jervois to Rajah Brooke, and was invited to stay at the Palace.

At the time the Rajah of Sarawak was Charles Brooke. He had succeeded his uncle James Brooke, the first Rajah of Sarawak; a former soldier and adventurer who after receiving a large inheritance bought a schooner with which he sailed to the Indonesian Archipelago. When he was in Borneo, he twice helped to suppress a rebellion against the Sultan of Brunei and was rewarded for his services by being made the Rajah of Sarawak. He and two of his descendants, ruled Sarawak from 1842 until 1946 when Sarawak was ceded to the British crown. One of James Brooke’s many visitors was the famous naturalist, anthropologist, geographer and explorer Alfred Russell Wallace (1823-1913) who created the famous faunal boundary line in Eastern Indonesia known as the Wallace Line, and whose work was of great help to Charles Darwin.

From her verandah at the Palace, Marianne North was dazzled by the views of the Palace gardens, the river and the mountains. The vegetation which included orchids and pitcher plants, entranced her. In her diaries and letters she writes enthusiastically about such plants as the sago palm which she wrote takes 15 years to flower and then is cut down before it can bear fruit in order to take out its pith which provides enough sago for one man for a whole year, according to Wallace. To North at times, the plants were almost like people. She describes how rattan creepers bound all the greenery of the forest together with their long, wiry arms and fish-hook spines. She then comments how she traced one rattan far up into the high trees, and adds with typical humour, “No growing thing is more graceful or more spiteful.”

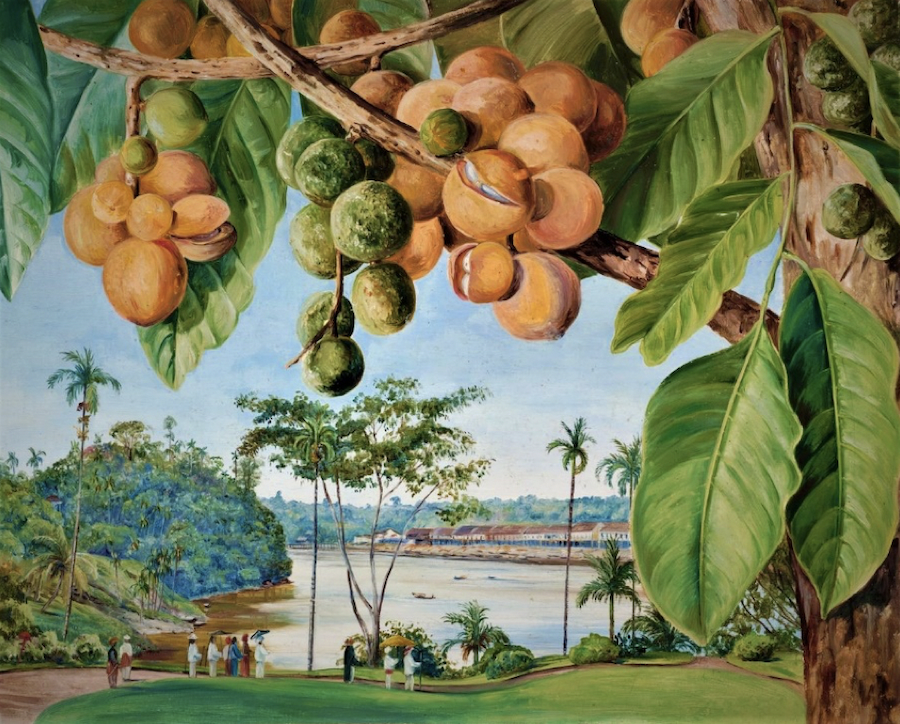

North writes with pleasure about tropical fruit especially the mangosteen whose fruit she describes as looking like, “lumps of snow, melting in the mouth with a grape-like sweetness.” Strangely though, she apparently preferred the duku; a preference which famous French novelist, Jules Verne who described mangosteen in his book ‘Around the World in 80 days’ as the finest fruit in the world – would not have agreed with.

After having spent some weeks at the Palace, North went to the Rajah’s mountain-farm in the Matang Forest where she painted the recently named Chassalia northiana. The Rajah sent her off in a canoe with a cook, a soldier and a boy, lots of bread, and a coopful of chickens. They paddled through small canals in the forest all day and then landed at a village and climbed up 700 feet to a clearing in the forest where the Rajah’s farm and cottage were located. She described the view as wonderful, “… with the great swamp stretched out beneath like a ruffled blue sea, the real sea with its islands beyond, and tall giant trees as foreground around the clearing.,”

She then adds that, “I could not help painting. Life was very delicious up there. I stayed until I had eaten all of the chickens, and the last of my bread had turned blue…”

Later, North describes how after leaving Tegoro she ventured out in a canoe, shooting over the rapids for many miles at a terrible pace, the local people cleverly guiding the canoe with their sticks and paddles – all the-while with great trees full of flowering epiphytes arching over the river. She disembarked and walked through a wonderful limestone forest until they reached an antimony-mine where she stayed to paint the flora. Meanwhile, one of the men climbed up a nearby mountain and returned trailing specimens of the largest of all pitcher plants. North painted it and her painting inspired John Gould Veitch (April 1839 – 13 August 1870) to later send someone there to look for the seeds which he then raised to adult plants. Veitch was a British horticulturist and one of the first European plant hunters to visit Japan. North wrote, “The pitchers are often a foot long and richly covered with crimson blotches.”

Later, it was discovered that the pitcher plants which she painted were a new species. The 19th century British botanist and explorer, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817-1911) named the new species Nepenthes northiana, after Marianne North. (Tamalia Alisjahbana)

If you enjoyed this article you may like to read more about Marianne North by the same writer in:

Part II: https://observerid.com/marianne-north-19th-century-botanical-artist-and-her-indonesian-travels-and-paintings-part-ii-her-travels-in-java/