IO – The house in Tugu has always been associated with roses. I still look for the old fashioned roses from the Dutch times (or perhaps they are from an even older period and the Indian or Arab traders brought them – who knows) that through the years became acclimatized to Tugu’s climate and environment in the mountains of West Java. Amongst them were the rambling, pink briar roses which now grows up a Himalayan cherry tree that I purchased years ago at the Cibodas Botanical Gardens. My father used these as a base to graft other roses. I was the only child interested in learning grafting from him but the roses always disappointed me a little. They were never that strongly scented.

One day, driving slowly along the Cibodas Botanical Garden road which is lined with plant sellers, I stopped at the small house of one man who only sold roses. He was passionate about them and had many imported roses with which he tried to tempt me but I was never interested in what I consider weak, disease prone roses unsuited to Tugu. That day he said, “Wait. I have a rose that you do want – a Persian rose,” and he dashed back amongst his roses. Intrigued, I waited and he came back with a single pink blossom and laid it in my hands with the words, “You want this rose. Smell it.”

I lifted the rose to my nose and was over whelmed by a powerful, sweet scent. I had never smelt a rose so strongly scented. It was a rich and beautiful scent. Henry James once said that his favourite words were, “summer afternoon” and that is what that rose smelt of to me: a European summer afternoon. The rose seller was right. I wanted that rose.

Some weeks later, I was on a flight to Europe and beside me sat a young Iranian gentleman who had a large bag of pistachios and raisins that we consumed as we talked through the night. He told me that he had escaped from Iran fleeing over the mountains through Afghanistan to Pakistan until he finally reached Canada where he now lived. He was in Indonesia to sell wheat. “I am a Pashtun. So, the Afghans helped me through the mountains,” he explained.

Later, we spoke about Iran and somehow the conversation led to the beautiful roses of Isfahan. “They are the best in the world,” he said and I told him the story of the rose seller of Cibodas and the powerfully scented Persian rose. He smiled and said, “That rose is called Gul-i Mohammadi (Rosa damascena) which means ‘the flower of Muhamad’ for it was said that when the Prophet perspired his perspiration was so sweet it turned into roses.”

My father, Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana was a member of parliament for the Partai Sosialis Indonesia or Indonesian Socialist Party, usually abbreviated to PSI. Many of the writers contributing to and editing his literary journal Konfrontasi (meaning ‘Confrontation’) were members of the PSI or PSI sympathizers as were the members of the Konfrontasi Studi Klub which met regularly at the house in Tugu for discussions, especially literary and cultural discussions.

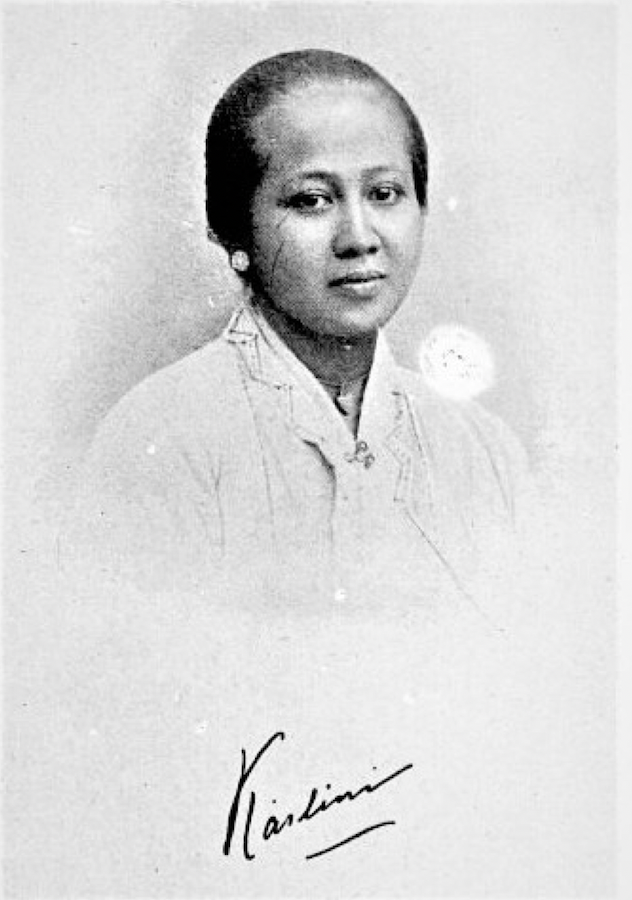

There has always been a tendency amongst PSI men to be a little in love with Indonesia’s most renown women’s emancipator, Raden Ajeng Kartini. The PSI was the intellectuals’ party so it is not really surprising that they gravitated towards women who were educated, intelligent and with whom they could have intellectual discourse – and Kartini exemplified that sort of a woman. These were the sort of wives they looked for and the typical heroine or at least woman to whom to aspire to, in a PSI novel were such women. We see this for example in Mochtar Lubis character Iesye in his book ‘Twilight in Jakarta’ and in Toeti in Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana’s Layar Terkembang or ‘With Sails Unfurled’.

Raden Ajeng Kartini was born in Mayong, Central Java in 1879 and came from a Javanese aristocratic family. Her father who was the Bupati or Regent of Jepara was very progressive, and unlike most of the Javanese aristocracy of the time he allowed her to go to a Dutch school until the age of twelve. After this, like most aristocratic young girls she was forced into seclusion and restricted to the house.

Kartini had a very intelligent and active mind, with a great curiosity about the world. This was coupled with a sensitivity towards people, places and events which must have made her seclusion extremely depressing and hard to bear. She compensated for it by turning to books, newspapers and magazines and in a diligent correspondence with people of various classes and fields, many of whom were amongst the most prominent figures as well as the leading intellectuals of her time. Kartini’s father received diverse visitors and allowed her to meet them. A number of them became close friends. Included amongst these were Jacques Henry Abendanon, the Minister of Education, Religion, and Industry of the Netherlands East Indies and his wife, Rosa. There were also Henri Hubertus van Kol, a Socialist member of the Dutch parliament and his wife Nellie who was a humanist and feminist writer. Kartini also corresponded with Hilda de Booy-Boissevain whose father was the director of the Algemeene Handelsblad, an important daily at the time, and whose husband was adjutant to the Governor General – these were just a few of her more important friendships. There were many more.

Kartini had a dream that completely consumed her and that dream was education for women. She dreamt of going to Holland and getting a teacher’s training degree and then returning to Indonesia and opening schools for girls. In the end her dream materialized: The Socialist Party in the Netherlands fought for her to obtain a scholarship and her father despite great disapproval from the other regents gave her his permission to go to Holland. There was an intoxicating moment when that dream was within her grasp and then something totally unexpected happened.

Abendanon, the Netherlands Indies Minister of Education came flying over unexpectedly to Jepara, and took her for a walk along the beach. When she returned she agreed to give up her scholarship. Why she did so is another story (see: https://observerid.com/in-defence-of-kartini/) but she did not live many years thereafter and died at the age of 25, not long after giving birth to a son. There the story might have ended but Abendanon later collected and edited many of the letters she had written to so many different people filled with her sensitivity, penetrating thoughts, ideas and idealism. They are amongst the most beautiful and extraordinarily wise letters to have ever been written by an Indonesian. My father used to refer to Kartini as Indonesia’s first modern intellectual. Abendanon had her letters published in a book entitled Door Duisternis tot Licht or ‘Through Darkness Towards Light’ which became a bestseller and was translated into many languages. It also opened the floodgates for women’s education in the Netherlands Indies.

At the time, very few Indonesians (not only women but also men) were able to receive an education and education was something that the PSI not only very much valued but considered almost sacrosanct. Its members were the intelligentsia and amongst the very few who were able to get that education. Consequently, they identified very much with Kartini’s struggle and ideals. Her story inspired them and for many PSI men she represented the ideal woman.

In my father, this tendency was especially strong. Some years after the death of his first wife, my father remarried – and his second wife, Raden Roro Soegiarti was his Kartini. She was a very intelligent and sensitive woman who helped edit Pujangga Baru as well as occasionally contributing to it. As a very young child my father had witnessed his mother being beaten by his father and saw how she endured this simply standing with her head bowed and tears rolling down her cheeks. That little boy could not bear to see this and promised himself that as soon as he had the money, he would take her away from that place where she was neither loved nor valued. This finally happened when he finished his studies and became a teacher in Java. He used his first salary to send her a postal order with the funds to come and join him in Java. In the return post he received a letter saying that she had just died, and that the money he had sent had been used to bury her.

My father was so overcome with grief that it physically affected his heart and he had to stay for several months in a sanitarium in the mountains not far from Tugu. This predisposed him towards viewing women and their sorrows and struggles for equality, with a deep sympathy. Later, I found amongst my father’s papers, documents from the Indonesian women’s movement and as children we were all sent to Perwari (Persatuan Wanita Republik Indonesia or the Indonesian Women’s Union) schools. He reached the same conclusion as Kartini namely, that the best way to protect women from abuse was by educating them.

He had also something else in common with Kartini. My father was born with a deformed left hand which he always covered with a handkerchief or hid in his pocket as the other children teased him mercilessly about it. As a result, like Kartini he was also in a sense isolated growing-up and like her he dealt with the consequent loneliness, by writing. It was a way of channeling the pain, the loneliness and sadness that life can inflict on us. After his mother’s death while in the sanitarium, he wrote his first novel, Tak Putus Dirundung Malang or ‘Unending Sorrows’.

In a way it could be said that Soegiarti, my father’s second wife, lived Kartini’s dream for she managed to obtain that scholarship to go to Holland to train as a teacher that Kartini had dreamt of. This made her one of the most educated women in Indonesia at the time. Added to this, she obtained her scholarship with the help of Kartini’s famous brother, Raden Mas Panji Sosrokartono. My father met Soegiarti while giving her Indonesian lessons. Malay was chosen as the basis of Indonesia’s national language in the Youth Pledge of 1928 but many Javanese nationalists could not speak Indonesian (other than a rough Malay used in the market place) and Sumatrans like my father and Amir Hamzah (who also met the love of his life while giving her Indonesian lessons) frequently acted as private language tutors. If there is still any doubt that my father saw Raden Soegiarti as his Kartini then ‘Defeat and Victory’ should put that to rest. In this book the figure of Hidayat is based on my father and Hidayat’s wife is Raden Soegiarti. In the book my father gave her the name, Kartini.

Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of American President Franklin Roosevelt later wrote a preface for the English translation of Door Duisternis tot Licht. In English it is called ‘Letters of a Javanese Princess’. Although, I do not think Mrs Roosevelt actually visited the Tugu house, I once saw photographs of her in Tugu during her trip to Indonesia in 1952. My sister Mirta says that she was together with one of the Indonesian women’s groups and Soegiarti was there. I remember thinking that the house looked like one of the houses (now a Ministry of Communications guest house) that once belonged to a former member of one of the German U-boats stationed at the German U-boat station in Surabaya during the War. After the War, Sam Berger lived in Tugu not far from our house and used to sell us milk, butter and eggs from his farm.

And finally, to return to the subject of roses. Like my father, Kartini also enjoyed nature and gardens. She loved roses and like him, also found comfort in their symbolism. So, I shall end here by quoting her on the subject of roses. In ‘Letters to a Javanese Princess’ she writes about how after the heavy rains she feared that the roses in her garden would be destroyed but found instead that the rose bushes were full of green buds and as the days continued these became luxuriant leaves and beautiful blossoms. She writes, “Rain, rain, they needed it, before they could bear those splendid blossoms.

Rain-rain- the soul needs it in order to grow and to blossom. Now, we know that our tears of today, serve only to nourish the seed, from which another, higher joy will bloom in the future.

Do not struggle, do not complain and curse sorrow when it comes to you. It is right for sorrow to exist in the world too; it has its mission. Bow your head submissively before suffering. It brings out the good that is in the heart. But the fire which purifies gold, turns wood to ash.” (Tamalia Alisjahbana)

If you enjoyed this article you may like to read more about the house in Tugu by the same writer in:

Part I: https://observerid.com/the-house-in-tugu-and-its-literary-circle-part-i-how-it-began-and-hella-haasse/

Part IV: https://observerid.com/the-house-in-tugu-and-its-literary-circle-part-iv-the-indonesian-writers/

Part V: https://observerid.com/the-house-in-tugu-and-its-literary-circle-part-v-the-new-german-mother/

Part VI: https://observerid.com/the-house-in-tugu-and-its-literary-circle-part-vi-beb-vuyck