IO – One thing that attracted my attention in the garden of the Tugu house were the plants that kept changing their colours until reaching a final colour, before obtaining full maturity. The handkerchief tree (Maniltoa lenticellata) is native to Bintuni Bay, Papua. Its leaves begin by coming out in distinctive clusters of pale pink which turn which white then pale lemon green and finally the dark green of mature leaves. Another is Brunfelsia pauciflora or ‘Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow’ which has highly scented blossoms that come out purple and then change to blue and final white before dropping off the shrubs. In Tugu there are also the mulberries that come out almost white, then turn pink, later red and finally ripe, sweet and black. The most striking though is the double Rose of Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus). A friend of mine told me once how she saw a white one placed on a dinner table as a centre piece and how within an hour it had turned pink – turning it also into a conversation piece.

To my mind we human beings are somewhat like these plants. People have very different histories and cultures and ways of viewing the world. Sometimes, we meet others and evolve our views; we change our colours a little or a lot, so to say. At other times meanwhile, we remain more or less the same, even after encounters with very different people. This was the case with the American Black writer, Richard Wright who the Congress for Cultural Freedom sent to Indonesia and put in touch with the Konfrontasi Study Club. They were mismatched from the start and I do not think either side ever really understood where the other was coming from.

In 1955, the Black American writer, Richard Wright came to Indonesia to attend the Asia-Africa Conference held in Bandung that year. After the conference, he went up to the house in Tugu where he stayed overnight and gave the Konfrontasi Study Club a lecture entitled ‘American Negro Writing’ which Konfrontasi magazine published in its May-June 1955 issue. It is the first known English language publication of his’ White Man Listen!’ lecture.

Richard Wright like my father was born in 1908. In one of his best works ‘Black Boy’ published in 1945, he describes his life in Mississippi from the age of four till nineteen and the racism and violence that he experienced growing up. Despite being very intelligent and a good student, for economic reasons Wright was only able to finish lower high school. At the age of 19 he moved to Chicago and later, to New York. Wright received first national recognition with his book ‘Uncle Tom’s Children’ which contained four short stories that included such themes as the lynching of Blacks in the South.

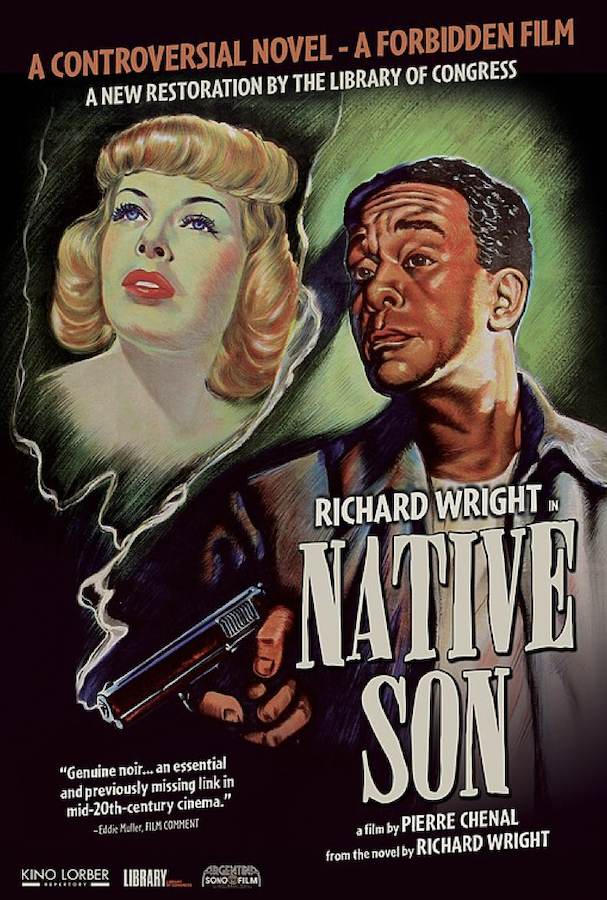

Sometime later, Wright wrote ‘Native Son’. Here, the main character Thomas Bigger is born into a deep poverty in Chicago which creates enormous tensions within him. He is only able to release those inner tensions by acting them out in the form of abhorrent crimes. Some criticized Wright’s focus on depictions of violence and for portraying his main character as the sort of Black person, White people most feared. James Baldwin, another Black writer identified Bigger as a stereotype and not a real character. What Wright was trying to convey in fact, was that Blacks are the product of the society that formed them and that since birth has been conveying to them who they are meant to be.

Wright’s work centres around the suffering of Black Americans due to the discrimination and segregation brought about by the racism and violence against Blacks in America. It was his experiences in Mississippi, Arkansas and Tennessee that formed his impressions of American racism. His work inspired the civil rights movement in mid-20th century America. Wright later went into exile to Paris and eventually obtained French citizenship. There he formed friendships with writers and thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus and Simon de Beauvoir.

The Asia –Africa Conference was held from the 18th till the 24th of April 1955 and Richard Wright gave a lecture to the Konfrontasi Sudy Group on the 1st of May 1955 at the house in Tugu. Richard Wright was sent by the Congress for Cultural Freedom with which many of the members of the Konfrontasi Study Club were associated especially, Mochtar Lubis but also people like my father, Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana, Soedjatmoko, Asrul Sani and others. Cultural freedom and democracy were things that both the Konfrontasi Study Club and the Partai Sosialis Indonesia very much prized.

The Congress for Cultural Freedom or CCF was established when a number of intellectuals from around the globe created an organization in 1950 intended to form an international intellectual community that promoted democratic and free expression in speech, writing, culture and thought. It was anti-totalitarian in its nature. The CCF funded the publication of books and travel and held conferences and concerts but its most important work was sponsoring the publication of a large number of magazines and journals in six continents. Its flag ship magazine was Encounter which was published in the United Kingdom.

It was only sixteen years later that the CCF was criticized for having received funding indirectly from the CIA and because its director, Michael Josselson had been commissioned by the CIA to set up the CCF. However, more recent writers of the 21st century such as Greg Barnhisel, Hugh Wilford, Giles Scott-Smith and Charlotte Lerg question how large the CIA influence in fact was on the CCF and its magazines. Their years of research show that Josselson was as loyal to the CCF as he was to the CIA and that he did not want the CCF to be used for espionage and very seldom interfered in Encounter’s publications or in other CCF magazines which could be critical of United States policies, as well as McCarthyism.

Patrick Iber in ‘The Spy Who Funded Me: Revisiting the Congress for Cultural Freedom’ writes that CCF ‘history cannot be reduced to one of CIA interference. The magazines that were effective in consolidating an intellectual community did so because underlying conditions produced groups of people receptive to the outlooks they represented’.

After the War few European writers, poets, artists, historians, scientists, or critics were not in some way linked to the CCF. At any rate the Konfrontasi Study Club who were mostly Indonesian PSI members and sympathizers had no idea about any CIA involvement at the time, and much later when people like Mochtar Lubis who later sat on its board, became aware of CIA involvement he was among those who insisted that the CCF no longer accept such funding and that Michael Josselson leave the CCF.

Most members of the Konfrontasi Study Club were either members of the PSI or PSI sympathizers. Their creed was universal humanism which of course, made them supporters of democracy without which universal humanism cannot exist. Perhaps the simplest way to explain a human universalist is to describe what was once said of Sutan Sjahrir, Indonesia’s first prime minister, the leader of the PSI and a cousin of my father. It was said of him that he was not merely a nationalist in the sense that had the Netherlands been an Indonesian colony struggling for freedom, he would have been on the side of the Dutch. He himself went to the Tugu house and one of his anak angkat or adopted children, the former Orang Kaya of Banda, Des Alwi once showed me a film of Sjahrir at the Tugu house with his children having fun swimming in our very cold swimming pool.

One could say that the Congress for Cultural Freedom sent Richard Wright to the wrong group. He and the PSI were totally mismatched. Wright would probably have felt far more comfortable and found himself sharing a more similar perspective, with the communists or even perhaps the nationalists, rather than the socialists. Although, Wright had by then repudiated the Communists, he had for a time been a member of the American Communist Party and in many respects still sympathized with their view of society. The Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat or Lekra, an institution of the Indonesian Communist Party or PKI asserted that a writer must hold a world view of people–mindedness (as opposed to individualism) and (as expressed by Roberts and Foulcher in Índonesian Notebook’) that his writing should expose social ills and revolutionary aspirations through an uncompromising realist aesthetic. Wright’s novels of social protest of course fitted this description. He believed that a writer must strive to be a part of the people’s struggle for justice.

This left the Konfrontasi group in a difficult position as they were then under heavy criticism and pressure from Lekra with the growing influence of the PKI in national politics. Nevertheless, Konfrontasi accepted Wright as an important writer not only for America and its black people but also internationally, and were able to extend themselves and embrace this by putting forward the human universalist view that the value of a work of literature is seen in its reflection of the life of man and the ups and downs of man’s life through writings that express the heart of the writer which they accepted as reflected in Wright’s work.

Richard Wright was brought up in the American South and had lived through terrible experiences of the racism prevalent there. He was one of the most important and influential Black writers of the mid-20th century. Racism and inequality were subjects that he was passionate about and for him, the colonized nations of Asia and Africa reflected this destructive racism and thus the Asia Africa conference was of great interest as a movement towards erasing such racism.

Like many African American intellectuals at the time, Wright viewed leaders like Sukarno and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana who became very authoritarian as great men whose anti-colonial struggles were an inspiration and model for their own struggles with racism and discrimination in America. The members of the Konfrontasi Study Club on the contrary held no admiration for either leader and believed they needed to be resisted.

As socialists, of foremost importance for the Konfrontasi group was the economic welfare of the people. In his book, ‘Indonesia Social and Cultural Revolution’ Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana described Soekarno as foremost an artist and a politician with little talent as an administrator or economist. The PSI watched with growing dismay as the Indonesian economy grew increasingly worse. By the time Soekarno fell from power there was over 600% inflation and starvation in parts of Indonesia. Most of the plantations that had made the Netherlands Indies so rich had fallen into a state of neglect and Indonesia’s infrastructure was in disrepair. In his book, Takdir described Soekarno as a monumentalist who was engrossed with what in Indonesia is referred to as proyek mercusuar or ‘lighthouse projects’. These are monumentalist projects such as building the largest stadium or water fountain at the time, as well as the many statues and monuments around Jakarta when so many Indonesians were living below the poverty line.

Consequently, most of the Konfrontasi Study Club were not very impressed by the Asia Africa Conference which they tended to think of as another monumentalist project dragging attention away from where in their opinion the government’s attention really ought to have been namely, Indonesia’s economy and the welfare of the people. These perspectives immediately placed them at odds with Richard Wright.

What was most important for the socialists after economic welfare for the people was democracy and freedom of speech. This is why so many of them were involved with the CCF and why they were dismayed by Sukarno’s increasing authoritarianism and the rise in influence of the Indonesian Communist Party. Wright on the other hand, was comfortable with the idea of strong leaders such as Sukarno and Nkrumah who put aside the pragmatism needed to bring about the economic welfare of their people as well as democracy.

Wright had great difficulties in understanding Indonesian and especially PSI’s experience with racism for it differed so markedly from his own. In the 1950s the struggle of Black Americans against discrimination was far from over. In fact, in the 1960s Martin Luther King would just be starting the black civil rights movement in America. Indonesians were at a very different stage. They had managed to win the war of independence and were now in power and ruling their own country. Also, the PSI members represented Indonesia’s intelligentsia. They were the lucky few who had managed to get that precious education that was so pivotal in obtaining Indonesian independence. It was also a very good quality education for the Dutch professors who lectured in Indonesia later lectured at the best universities in the Netherlands. PSI members had no doubt also experienced some racism during the colonial era but most of the Dutch that they came in contact with were academicians, journalists and socialists – these are usually the most liberal members of society. They would have been the segment of Dutch colonial society most likely to treat them without discrimination This was an experience so different from that of Wright’s that it made it very difficult for Wright to believe them when people like my father told him that they did not feel a sense of inferiority towards white people. In fact, Wright got into a furious argument with Sitor Situmorang about this point. They on the other hand, viewed Wright as obsessed with race issues.

Brian Russell Roberts and Keith Foulcher have document the whole visit by Wright and what in fact happened very clearly and objectively in their book, ‘Indonesian Notebook: A Source Book on Richard Wright and the Bandung Conference’. Wright first wrote an account of his visit in Encounter magazine entitled ‘Indonesia Notebook’ in 1955 and Indonesisches Tagebuch in Der Monat and finally, ‘The Color Curtain’ in 1956. The members of the Konfrontasi Study Club who attended his lecture in Tugu were angry with what he wrote because Wright misrepresents and distorts many of the things that the members of the Konfrontasi Sudy Club said during his visit to the Tugu house. Perhaps, what left the members most angry was that he created a nameless composite character whom he described in such a way that no one would doubt that he was referring to Sutan Takdir Alisjahban however, he has the character admit that he feels inferior to White people and he has him refer to the Japanese as ‘yellow monkeys’. In fact, it was Sitor Situmorang who told a story about how badly the Japanese treated ordinary Indonesians during the Second World War and how much hatred there was of them. It was he who quoted a village head referring to them as ‘yellow monkeys’. Anyone who has read ‘Defeat and Victory’ will know that my father had no prejudices against the Japanese. It was Wright who had no understanding of the horrors of the Japanese Occupation that so many Indonesians had experienced. He simply saw Indonesians and Japanese as both being colored people and therefore that they ought to feel a sense of commonality.

Mochtar Lubis protested Wright’s account in a polemic of letters with Wright published in Encounter and Beb Vuyck set the record straight in her own account, ‘A Weekend with Richard Wright’ published in the Dutch periodical Vrij Nederland. Wright does not appear to have understood the distinction between journalism and writing a novel. In writing a novel the author may create fictional or composite characters who say things in line with the author’s storyline. In journalism that is anathema. A journalist may only report facts.

What made this especially abhorrent for the members of the Konfrontasi Study Club is that many of them were journalists. A journalist of integrity may not make things up but must report exactly what he sees and hears. Although, Wright wrote his report in periodicals as a daily diary reporting what happened during his Indonesian travels, he did not in fact write it as a journalist but rather as a novelist. It has been said of Wright that for him his art was sacred. He did not care about anything else but that. He also believed as did Lekra, that a novelist should be exposing social problems and struggling for a cause. So, creating a composite character and clearly indicating that he was Takdir and then having him say things that were the opposite of what Takdir said or that Takdir never said for the sake of the cause – was simply poetic license for Wright. For the journalists in the Konfrontasi group it showed dishonesty and a clear lack of integrity.

The only person of whom there is no record of having either written or said anything about it was my father. When I found Wright’s ‘Native Son’ amongst his collection of books in the Tugu house Takdir merely commented, “He was an American writer who wrote about the struggle of Black people in America and he visited Tugu once.” (Tamalia Alisjahbana)

If you enjoyed this article you may like to read more about the house in Tugu by the same writer in:

Part I: https://observerid.com/the-house-in-tugu-and-its-literary-circle-part-i-how-it-began-and-hella-haasse/

Part IV: https://observerid.com/the-house-in-tugu-and-its-literary-circle-part-iv-the-indonesian-writers/

Part V: https://observerid.com/the-house-in-tugu-and-its-literary-circle-part-v-the-new-german-mother/