Jakarta, IO – For the past year, the price of cooking oil has been steadily rising. And since early 2022, it has surged uncontrollably. The spike in domestic cooking oil prices was sparked by the steep rise in international oil palm prices. The price of oil palm (CPO) has increased in the last two years due to several factors. First, the Covid-19 pandemic which caused severe disruption in the supply chain of various goods and services, including palm oil. After the pandemic subsided, there was an increase in demand amid the supply crunch.

Second, the Quantitative Easing (QE) policy implemented by almost all countries, especially by the world’s four major economies (the US, EU, Japan and China) which increased the money supply from US$ 15.4 trillion in 2019 to US$ 24 trillion in 2020 and further to US$ 24.5 trillion in 2021. Figure 1 shows the link between the rise in CPO prices and the amount of QE carried out by central banks of the four countries. Third, amid limited supply, various countries, including Indonesia, continue to pursue new and renewable energy programs as part of the Paris COP21 commitment hatched in December 2015 to reduce global warming and mitigate climate change through the use of biofuels made from edible oils, including oil palm. FIGURE 1

Many experts predicted the oil palm prices would gradually decline in 2022. However, the Russia’s military offensive against Ukraine has shattered this projection. Prices of various commodities, especially those related to energy and food are expected to keep rising. This is due to the fact that Ukraine is the world’s largest producer and exporter of sunflower which is widely used in the EU as the raw material for biofuels and industry. Meanwhile, Indonesia’s palm oil exports to Russia and Ukraine, although not too large, are significant for Eastern European countries. Due to the Russo-Ukrainian conflict, the world’s supply of vegetable oil is increasingly limited so prices will remain high, perhaps even higher than the previous years. On the other hand, Indonesia’s exports to these countries will also be disrupted.

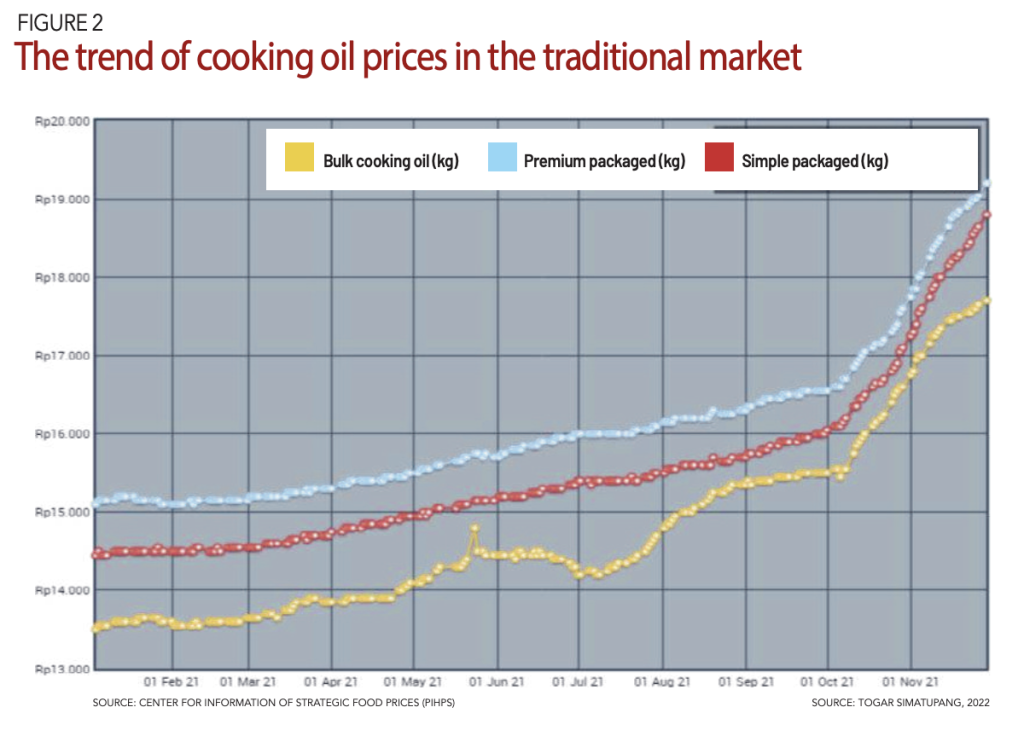

As oil palm is a widely traded commodity in the international market, the domestic oil palm prices will follow the global price. As a consequence, it has also increased sharply. About 80% of the cost of cooking oil comes production comes from oil palm. As can be seen from Figure 2, cooking oil prices rise in tandem with oil palm prices. However, there were also non-economic factors that drove this, especially after the government implemented a series of policies to try to bring down the price. First, an allegation of cooking oil cartel manipulating the production volume and thus the price of cooking oil in the market. This allegation has yet been proven even though the Business Competition Supervisory Commission (KPPU) is currently investigating this matter. Second, a panic buying phenomenon in the society driven by fears of supply shortages. However, the consumers can’t be blamed given the acute shortage of cooking oil in various regions. Third, the alleged hoarding of cooking oil by irresponsible actors. Although this kind of behavior, if this is the case, is caused by government policies that create disparities in cooking oil prices. FIGURE 2

The government has issued a flurry of policies to tackle the rising prices and scarcity of cooking oil in the market. First, on January 11, the Trade Ministry issued Decree 1/2022 to increase the supply of packaged cooking oil through various distribution channels, both modern retail and traditional markets through a financing scheme from the Oil Palm Plantation Fund Management Agency (BPDPKS). Second, on January 18, the Trade Ministry enacted Decree 2/2022 to implement the Domestic Market Obligation (DMO) policy for CPO, RBD palm olein, and used cooking oil (UCO) exporters. This was followed by Decree 3/2022 on January 19 that set the retail price of cooking oil at Rp14,000 per liter in traditional markets and modern retail channels. Not stopping here, it then issued Decree 6/2022 on January 26 which imposed retail price cap (HET) for bulk cooking oil at Rp11,500 per liter, simple packaged at Rp13,500 per liter and premium packaged at Rp14,000 per liter effective from February 1. This was followed by Decree 8/2022 on February 8 which imposed DMO of 20% and Domestic Price Obligation (DPO) of Rp9,300 per kg for CPO and Rp10,300 per kg for RBD palm olein. The DMO was later increased to 30% of export volume. This means exporters can only export after meeting the requirement to supply 30% of their export volume for domestic market at the said price level.

After more than a month since the DMO and DPO policies took effect, the price of cooking oil in the market has not gone down as expected by the government. It still hovers at Rp16,000 per liter, higher than HET. This is exacerbated by shortages of supply in various regions as per various media reports. Purchases are rationed to only two liters per person. Scenes of housewives queuing to buy cooking oil are common. In several areas, large crowd of people had to jostle one another to get their hands on cooking oil. A mother in East Kalimantan died in the middle of snaking queues. In North Sumatra, people from Sibolga had to travel a distance to Medan, the capital city, as stock vanished. There are many other cases of unnecessary sufferings. The point is, the DMO and DPO policies have been ineffective in solving the cooking oil crisis.

Why is the case? Many think the problem lies in the implementation of this policy, compounded by the lack of planning and preparation, inaccurate data, policy abuse by certain individuals and panic buying are all to blame. Lack of planning resulted in constantly changing policies, from the provision of subsidies that have yet to be implemented to DMO and DPO. Inaccurate and incomplete data caused further problems in the production and distribution to various regions. This is due to the fact that cooking oil, despite it being categorized as basic necessities, was not an administered commodity monitored and regulated by the government, save for its retail price. On the suspicion that the policy is being abused by certain shady actors is also not entirely baseless. The Food Stability Task Force found hoarding of cooking oil on small and large quantity in several areas. Several days ago, it was reported that 415 million liters of cooking oil were being sold abroad far above the domestic price. Also, human behavior that prompt people to stock up more than they need is a ground truth although this is purely psychologically driven by fear and anxiety that cooking oil supply will run out in the coming days.

Indeed, the culprit is the DMO and DPO policies themselves. They simply do not work. The main reason being they distort the market and create a price disparity between cooking oil designated for industrial purpose and those for retail and small industries. What happens then is this policy encourages the business players in the supply chain, both upstream and downstream, to engage in rent seeking and other illegal activities. This gave rise to allegations of diverting bulk cooking oil to large industries, smuggling and hoarding.

Another impact of this policy is that exports will decrease, and it is possible that the price of palm oil on the international market will accordingly increase. In addition, supply for independent cooking oil plants is disrupted because oil palm producers are not willing to sell lower than the domestic market price. Already, six oleochemical factories have closed and one of them has laid off 350 workers. Even the latest policy to increase DMO by 30% will only make cooking oil even scarcer, domestic prices remain stubbornly high, exports decline and international prices increase further. It doesn’t stop there, the perverse incentive to carry out illegal activities will become stronger and the market becomes more distorted.

Therefore, after having been implemented for more than a month, it is time for the government to review the policies and formulate a more appropriate one. The new policy should meet the following criteria: first, it has a small market distortion impact; second, it provides a more targeted subsidy scheme; third, it does not incentivize illegal activities and create moral hazard; and fourth, it has lower monitoring and supervision costs.

The proposed policy scheme had in fact been implemented, but because it was estimated that the planning and preparation would take longer while the problems became more acute, the policy was replaced by DMO and DPO. The original scheme was, first, the government with the support of business players would set HET for subsidized bulk cooking oil. Second, the fund will be taken from BPDPKS. Third, the consumption of bulk cooking oil will be carefully calibrated, projected at 2.4 million kiloliters per year. Fourth, subsidy is only given for bulk cooking oil consumed by the lower middle class according to eligible recipients database established by the Social Affairs Ministry. As for the upper middle class, it would be unfair if they are also subsidized as is the case with the current DMO and DPO policies. Additional expenses due to the increase in cooking oil prices would be insignificant for them. So the price of simple and premium packaged cooking oil should follow the market price. Fifth, the subsidy is the difference between the production cost and the retail price of bulk cooking oil. Meanwhile, cooking oil producers will get oil palm at market price. A targeted subsidy scheme like this will not distort the market and create moral hazard as is the case so far.

Implementing the targeted subsidy scheme necessitates good coordination between appropriate ministries/agencies. The policy to use BPDPKS funds requires approval from the Finance Ministry and the BPDPKS Steering Committee which usually takes time to make a decision. Since this is an urgent matter there is no reason not to expedite the process. Meanwhile, the database of subsidy recipients is at the hand of the Social Affairs Ministry. The subsidy scheme also needs to be designed carefully as an addition to the social protection assistance they have received so far. The Trade Ministry, in collaboration with the Statistics Indonesia (BPS), can accurately determine the amount of additional subsidies by calculating the consumption of cooking oil by the lower middle class.

This scheme is expected to ease the shortage of cooking oil in the market, while preventing moral hazard and various kinds of fraud and abuse perpetrated by different parties and eliminating the need for costly monitoring and supervision. It will reduce disparity between the consuming public and the industry, and there will be no more long queues and disheartening scene of people fighting over cooking oil. On the other hand, a targeted subsidy scheme will also deliver social justice. People who really need the commodity will get the assistance and protection while people who are better off financially can be made to pay more as the increase would not affect them as significantly. The essence of this scheme is that markets are not distorted, society is protected, and industry is not disrupted. The government does not need to allocate more resource to control the market that is too complex. No more arrests should be necessary. There will be no longer interference from organizations such as political parties wishing to be seen as champion of the people by selling cooking oil at discounted price which is actually not their job. Another important thing that needs to be done is to disseminate information and familiarize the general public with the scheme so they will understand it and get rid of widely held assumptions that the government is absent or does not care about the problem.

The holy month of Ramadan will definitely see prices of basic necessities increase, made worse by external pressures. Therefore, the government must act quickly and appropriately to take various steps to mitigate this problem. This is a formidable task because each commodity has its own problems. It cannot be one size-fits-all solution. However, as far as cooking oil is concerned, policy changes must be made as soon as possible so that during Ramadan there will be no more shortages and long queues over cooking oil.

Even though cooking oil is a basic necessity, its consumption and the amount of public expenditure is not as large as other key commodities, such as rice. As can be seen from Figure 3, the average per capita consumption of cooking oil is 0.35 liters per week or 1.4 liters per month. Expenditure for cooking oil is actually not large, amounting to only Rp3,760 per capita per week or Rp15,036 per month, according to National Social and Economic Survey (Susenas) conducted by BPS in 2021. FIGURE 3

Essentially, it should be easier to solve this cooking oil turmoil. The economic impact of rising cooking oil prices on the people’s lives is not too large compared to rice or other commodities. However, if the phenomenon of people queuing and fighting over cooking oil becomes a daily occurrence, this raises the question of whether the government has sufficient capacity to make and implement the right policies.