IO – The Habsburg Palace in Vienna which houses the Weltmuseum Wien or World Museum Vienna has a room called “Collectors’ Madness” which was inspired by Habsburg Archduke Franz Ferdinand II who described his collecting obsession as, “I suffer from museomania”.

As human beings began to use the horse to travel and learnt to build boats they began more and more to explore other lands where they met new peoples and new cultures which they found exotic, exciting and fascinating – and so they began to collect objects from these new cultures. Collecting brings joy to many, it brings knowledge and a renewed understanding not only of how large, varied and fascinating this world is but also how much cultures interconnect.

The reason the Weltmuseum exists in Vienna is because of the past collecting enthusiasm of many of the Habsburg royal family. Although the museum’s ethnological collections actually date back to the 16th century with the Kunst-und Wunderkammern or “Culture and Wonder Rooms” that were filled with exotic objects from distant lands with the advent of the voyages of discovery, in the “Collectors Madness Room” at the Hofburg we learn of three members of the Habsburg dynasty from the 19th century who were especially known for their enthusiasm for travelling and collecting and whose collections make up an important part of the Weltmuseum’s collections.

The first was Archduke Ferdinand Maximillian von Habsburg, who was the younger brother of Franz Josef, the last emperor of Austria. Maximillian who was commander-in-chief of the Austro- Hungarian navy initiated the Novara Expedition. The SMS Novara was a sail frigate which conducted the first and only expedition of the Austro-Hungarian navy to circumnavigate the globe between 1857 and 1859. It was a scientific and research expedition. During the expedition the ship stopped in Indonesia and brought back many objects of interest.

The second 19th century Habsburg collector was Franz Josef’s son, Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria who committed suicide in Mayerling in 1889. Rudolf was an avid hunter and amateur naturalist with an interest in ornithology and during the course of his life he made several journeys to the East including to Egypt, Turkey, Lebanon and Syria. During the course of his travels he brought back collections of objects which later formed part of the Weltmuseum.

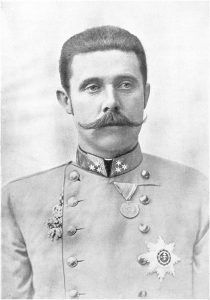

The third major Habsburg collector was Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Este. Most people think of him as the heir to the Habsburg throne whose later assassination in Sarajevo triggered World War I. What they usually do not know is that he was also an avid collector. In fact one of the rooms at the Weltmuseum Wien is named after Franz Ferdinand’s description of himself. The room is called Museomania or “Collectors Madness” and features a large display of Indonesian wayang golek puppets in front of which are displayed wooden heads with what appears to be different Indian head dresses and on the sides are decorated bamboo instruments. Behind all of these is a large photograph of the Archduke on his travels.

Weltmuseum Wien in the Hofburg Palace. (photo: Boedi Mranta Doc.)

The Weltmuseum consists of 14 rooms assigned to different subjects. One of them is the “Fascinating Indonesia Room” which houses ethnological collections from the Moluccas, Java, Indonesian Borneo or Kalimantan and Nusa Tenggara, from the Habsburg royal family as well as other collectors. The creation of the room was made possible by the sponsorship of another avid collector, this time from Indonesia: Dr Rudira Sudibja Boedi Mranata.

Dr Boedi was born in Banyuwangi in East Java. After finishing secondary school in 1969 he was sent to study biology in Hamburg where he specialized in aqua-culure and obtained his PhD. Upon returning to Indonesia he first worked in the field of aqua-culture and then switched to farming swifts for their nests which are mainly used by Chinese restaurants for birds’ nest soup. As this is a very lucrative line of business many people keep towers or buildings which are left dark except for small holes where swifts can enter to nest. Most people think that it is just a matter of luck if swifts are prepared to nest in a swift building but Dr Boedi says that is a myth and that a good biologist will know how to attract swifts quickly and in great numbers to his building. His business was highly successful and Dr Boedi received the nickname Raja Walet or “King of Swifts”. From there Dr Boedi diversified into other fields of business.

From an early age Dr Boedi Mranata was drawn to history and culture. He used to watch wayang orang or Indonesian puppet performances base on the Mahabharata and Ramayana epics as well as old Javanese court stories, until dawn. As a high school student he knew all the characters of the Mahabharata just as he knew the history of the old Javanese kingdoms of Singhosari, Majapahit, the unsuccessful invasion of the Mongolians and many other things. In Germany he read many books on Indonesian history and culture. After his return he began visiting antique shops. He was attracted to many objects but especially old furniture, ceramics and martavans. Slowly Dr Boedi began to collect.

Besides his fascination and love for the objects Dr Boedi also collects to help prevent all of Indonesia’s best cultural and historical treasures ending up with collectors and museums abroad. He feels that it is important that the best objects remain in Indonesia. In this sense he actually did the opposite when he bought a 19th century screen from Queen Juliana’s collection. It was made of European wood inlaid with ceramic plates from China. The sale was protested by various Dutch experts who said that the piece which clearly shows cross-cultural design, was a national heritage object and should not have been allowed to leave the Netherlands. The Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs however did not object and the screen is now in Jakarta.

Abu Ridho, the curator for ceramics at the National Museum in Jakarta became a friend and taught Dr Boedi more about ceramics. “I loved the stories behind the objects: how old they were, where they were made, for whom, during which dynasty etc. All these things fired my imagination nevertheless, the data regarding the objects had to be correct and with science and technology it is possible to know the true story behind a historical object,” remarked Dr Bordi.

Slowly, Dr Boedi became an expert himself especially with regard to ceramics and in particular martavans. He became head of the Indonesian Ceramic Society and wrote a book about martavans. Meanwhile, his collection of martavans (large ceramic jars usually made in China) became the largest in the world. He can now also be said to be the “King of Martavans”.

“There are people who say that the martavans which are mostly made in China are not truly part of Indonesian culture. I personally disagree with this. Most martavans were made in China and then exported to Indonesia. In China such martavans are simply used as containers. It was only in Indonesia that they were regarded as works of art looked at for their beauty. As they were also regarded as works of art, the Dayaks ordered more and more beautiful ones with better and better workmanship. The martavans they ordered reflected the Dayaks’ taste, culture and beliefs. If the Dayaks had not been involved in ordering them these martavans would not look as they do now. They are the product of two cultures and I think that these martavans are just as much a part of Indonesian culture as they are of Chinese culture.”

Amongst Dr Boedi’s great collection of martavans there are a few that hold a special place in his heart. He pointed to one and told its story. Dr Boedi buys his martavans from many dealers. One dealer, Haji Maruli would go by boat up the rivers into the interior of Kalimantan and then up tiny creeks which are tributaries to these rivers paddling by sampan often facing crocodiles and giant snakes. He set up a whole system for buying martavans with people bringing martavans to hubs that Haji Maruli created for collecting the martavans to places he could then visit.

Once while visiting one of these martavan collection points, a door was slightly open and he gazed into the room behind it and saw a highly unusual and rare martavan. When he asked to buy it the owner refused saying that the martavan had been passed down by their ancestors and that they were not allowed to sell it because of a vow that their ancestors had made long ago to never sell the martavan but keep passing it down to their descendants. The story is as follows:

In the past the Dayaks used to have a tradition that their men could only marry after having participated on a head hunting expedition and brought home the head of an enemy during a war. The head which had to be the head of an adult male would then be placed on a special tray or nampan during the wedding. During the wedding feast some guests arrived from another village who had not been specifically invited to the wedding but who were a friendly village to the village of the bride and groom. One of the guests from that village looked at the heads and suddenly demanded to know what the head of his missing neighbor was doing on the tray when the two villages had never been at war. To take the head of a person from a village not at war with one’s own village is considered a crime. The man returned to his village and told everyone what he had seen. Consequently, war broke out between the two villages. Peace could only be made if the offending village paid a fine so the village that suffered a loss asked for this very rare martavan from the offending village ‘s chieftain who refused and so the war continued for a long time with many victims. The village which was the victim of a murder then had a bright idea. They kidnapped the daughter of the head of the tribe in the offending village offering to trade her for the rare martavan. The trade was made and the war ceased but with the condition that the village that had suffered a murder had to swear that they would never sell the martavan but always pass it on to their descendants unless there were no more descendants and the line died out. At the time there was still a daughter with her child. Two years after Haji Maruli saw the martavan he suddenly received a message that the tribe were ready to sell the martavan. It appears that the daughter and her child had suddenly passed away. The new village head contacted Haji Maruli saying that the daughter had left instructions that the martavan was to be sold should anything happen to her and her child and that the money was to be used for ceremonies to pray for the souls of herself and her child. Haji Maruli then sold the martavan to Dr Boedi who feels that not only is it rare but for Dr Boedi it also holds a fascinating and very intimate story about the Dayaks and their culture and traditions which he values very much.

Recently Dr Boedi had a great gathering of family and friends for the Cap Goh Mei festival at his home. “It is to celebrate the coming of spring and the new plantings in the countryside,” he explained happy amongst the many guests admiring his collections. Dr Boedi has a place amongst the great collectors of the world. When asked what would happen to his wonderful collections once he was no longer there: would they be sold or would he create a museum for them or donate them to an existing museum? “I do not know yet,” answered Dr Boedi. “It still remains to be seen.” (Tamalia Alisjahbana)

If you enjoyed reading this article you may also enjoy Part I of the article by the same writer:

https://observerid.com/collector-budi-mranata-sponsors-the-indonesia-room-at-the-hofburg-palace-in-vienna/