IO – It is 60 years ago that Michael Rockefeller disappeared in the region of what was then still called Netherlands New Guinea but is now part of Indonesian Papua. He was with a Dutch ethnologist by the name of Dr Rene Wassing whom the Dutch government had appointed to accompany him, and two teenage Asmat young men by the names of Simon and Leo who were there to help run the boat they were on. They had gone out to sea on a two hulled catamaran consisting of two canoes tied together with a platform in between that had been given a tin roof and an 18 horsepower engine.

On the 18th of November 1961, they were at the mouth of the Eilanden River which is about three miles across. This is a dangerous place in November when there are strong winds and currents. That day, the outflowing tides of the river hit against the winds and currents creating great turbulence. A large wave hit the boat and flooded the engine, causing it to die out. They were adrift and the waters of the river were pushing them out to sea. Simon and Leo jumped into the sea to swim for shore which some accounts say was 3 miles away, while others claim it was only half a mile away from the shore.

Michael and Wassing remained in the boat in order to save Michael’s camera, notes and barter goods. Also, Wassing was not a good swimmer. The waves kept flooding the boat making it more and more unstable and finally capsizing it. Michael and Wassing then scrambled on to the hull to wait for help. Leo and Simon meanwhile, had managed to reach shore and arrived in Agats by 10.30 pm. By 1 am the Dutch authorities were making arrangements to find the two men.

By 8 am the next morning Michael decided to try to swim for shore as they were being pushed out to sea. According to some accounts the shore was about three miles away while other accounts say describe it as being about 12 miles away. Wassing tried to dissuade him but Michael slipped into the water and his last words were, “I think I can make it.”

It was the last time that Michael was known to be alive. The next day a Dutch seaplane rescued Wassing about 22 miles from shore.

Michael Rockefeller came from one of the wealthiest families in the world and was in Papua as part of a Harvard University Peabody Museum expedition. By the 23rd of November 1961 Michael’s father, Nelson Rockefeller who was Governor of New York had arrived in Papua with Michael’s twin sister Mary. Within 24 hours of his arrival, Nelson Rockefeller had boarded a DC-3 aircraft that he had charted, and aboard the plane searched 150 miles of the shoreline, using his binoculars to look for Michael with the plane often lowering to a distance of 250 meters from the ground, but found nothing. He went twice to the outpost of Pirimapoen, where he spoke to the Asmat and to the Dutch missionaries there.

The Dutch and Australian military in the area helped search for Michael. Rockefeller charted two helicopters from Shell Oil which was on the island, and over a thousand tribal Asmat canoes went out to search for Michael. A reward of 250 sticks of tobacco was offered as a reward for any evidence of Michael which was a fortune for the Asmat. The only evidence found was what was thought to be one of the red gasoline cans that Michael had tied to himself, by a Dutch naval ship out at sea.

After 9 days Nelson Rockefeller concluded that Michael could not have survived that long at sea, and the Dutch ruled his death a drowning. It was thought by the Dutch authorities that Michael had most likely drowned and that his remains had probably been consumed by a shark or crocodile. Nelson and Mary Rockefeller returned to the United States.

In the following years numerous articles, books and even a film were produced about Michael’s disappearance. One rumor was that he came ashore at an Otsjanep village, and was killed and eaten by the Otsjaneps who were seeking revenge after five of them had been killed by a Dutch district officer, three years before Michael’s disappearance. Milt Machlin, a journalist from Argosy magazine was the first to write about this rumor however, he was unable to find any proof. It remained speculation on his part.

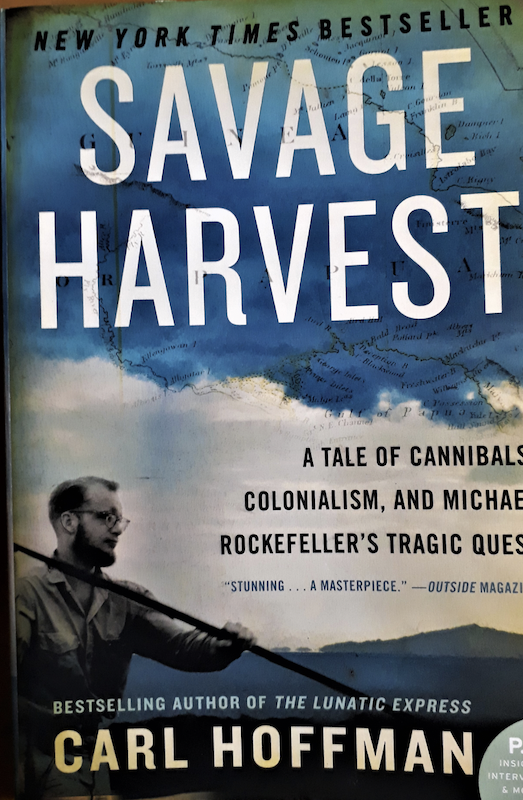

Then in 2014 Carl Hoffman, who had been an associate editor at National Geographic published his book ‘Savage Harvest,’ announcing that he had solved the mystery of Michael Rockefeller. He repeated the story that Milt Machlin had written but backed it up with interviews and reports from some Dutch missionaries who confirmed that they had been informed by several Asmats that that had been Michael Rockefeller’s fate. Hoffman also found reports from the Catholic Church as well as the colonial government confirming that this information had been reported to the Church as well as the government who instructed the priests to say nothing because the Dutch were involved in a struggle to keep Papua and needed to show the United Nations that they were capable of managing it well – which they apparently interpreted as eradicating headhunting, cannibalism and tribal wars.

So, why had the Asmats who were not known to head-hunt or to consume people who were not Asmat, have attacked Michael Rockefeller? Hoffman writes that it was retribution for the killing of five Otsjaneps by a colonial district officer named Max Lapre, in 1958.

Hoffman writes that there was continual warfare between the Asmat villages which included killing, headhunting and cannibalism in the 1940s, where hundreds of people were killed in such raids. The Dutch government began the pacification of the Asmat in 1952.

In 1956 Max Lapre was appointed controleur or district officer for Asmat. He was 30 years old. The incident that caused Lapre to pursue the Otsjaneps occurred at the end of 1957 when the Ostjaneps hid in their canoes at the mouth of the Etwa River and attacked a large party of Omadesep men returning home. They killed 113 Omadesep men and later decapitated them as revenge for the earlier killings of ten Otsjanep men by the Omadeseps. Lapre went with a group of armed Papuan policemen and warriors from another Asmat village not friendly to the Otsjaneps to investigate the killings. The Otsjanep warriors were armed, screaming and threatening and when one of them went running towards Lapre the Papuan policemen began shooting. Lapre ordered them to stop shooting but apparently 5 Otsjaneps were killed. Later in the book, Hoffman says that he was told that four of them had been the most important men in the village and suggests that Lapre deliberately targeted them. What he is suggesting is that Lapre deliberately ordered the most important men in the village to be shot. Is that truly what happened?

The report does not say that. The Otsjaneps killed 113 Omadeseps and beheaded them. This is a large number of people. What nation allows its citizens to do that unless it is in a state of war or chaos? It is the duty of governments to keep the peace and not allow warfare or murder. Governments deal with that in many ways but one of the most important ways is by sending out the police. Lapre went to the village to investigate but the tribesmen were not prepared to cooperate and his small police force was threatened by a very large group of armed and violent men who had killed over 100 people. Max Lapre was 32 years old and not very experienced. It was probably his first posting. It is very understandable if the police panicked and began to shoot. The Asmats go on raids using their boats. It is also understandable therefore that Lapre burnt the biggest boats before leaving.

Hoffman writes that Lapre’s action did not stop headhunting in Asmat. Of course, not. One single action would never be enough to change the traditional values of a people. That would require many different actions over an extended period of time by both the government as well as other institutions such as in this case, the Catholic Church which opened the possibility for new values. The twin instruments for social engineering are education and law and that would include police actions. Max Lapre himself later wrote, “Now with the pacification longer in place and the peace and security increasing, one sees clearly living conditions and relations changing and it is one of the government’s tasks to prevent the equilibrium in village communal life from being disrupted.

During the disturbances when villagers had to be mindful of the possibility of enemy attacks, it was the duty of the men to protect their village. Bearing arms, they would go into the jungle or fish with their women. Boats, weapons and other such things needed to be produced for the fighting that was to be carried out. Moreover, they were forced to live a nomadic life that required more work for strength in battle. So, the men had their special tasks which for the moment for the greater part disappeared. Now-a-days the villages are more or less permanent abodes; weapons are only needed for hunting, not so many boats need to be made because not so many are destroyed anymore as a consequence of war.”

This is what was known as the pacification of the Asmat and it took several years. The Indonesian government also does not allow tribal warfare, headhunting or cannibalism – and really, which government does?

On the 15th of March 2016, Carl Hoffman spoke in front of the Indonesian Heritage Society describing Max Lapre as a heartless Dutch colonial officer who had no love or cultural understanding of the Asmat in particular the Otsjaneps; in short, a trigger happy white colonialist with nothing but contempt for the Asmat.

Max Lapre was not such a person. I knew Max and his wife Etty, and frequently stayed with them in Holland. If I were asked to describe Max and Etty Lapre, the first word that springs to mind is ‘gentle’. They were both very gentle and kind people. Max was simply not a ruthless, arrogant white colonialist. Hoffman describes Max in his book as a white dot in an utterly foreign black-skinned world, that his whole life had been formed as a colonist and overlord and that he was determined to teach the natives a lesson in the power of civilian government.

Max was never a white dot amongst black dots. For all his research, what Hoffman missed was that Max was not white. He was Eurasian. A Dutch family does not live in Indonesia since the 17th century without mixing with the local people. Max came from generations of mixed race people, as did his wife Etty. Hoffman writes disparagingly about Max’s subordinate Dias whom he describes as a colonial mutt, half-Indonesian, half-Dutch, as though this were how Max would have viewed him, not realizing that Max himself was just such a ‘colonial mutt’.

Contrary to Hoffman’s descriptions Max and Etty Lapre cared about the Asmats, and they loved their time in Papua. They spoke of it often, as the happiest time in their lives, describing the Otsjaneps and Omadeseps with great affection. Like many Eurasians they loved both sides and were heart-broken at having to leave Indonesia, the land of their birth and their ancestors. Returning to Papua was a chance to return to a part of a land they cherished.

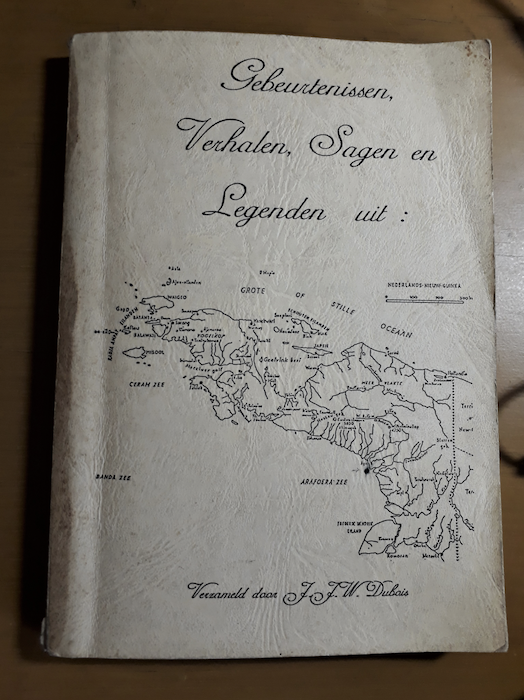

Hoffman described Lapre as a man who knew nothing of Asmat culture. This shows a lack of knowledge, for Dutch colonial officials like Lapre were schooled in anthropology and language before setting out for areas such as Papua. Max gave me a book entitled “Happenings, Stories, Sayings and Legends from Netherlands New Guinea” with chapters written by different district officers about their areas in Papua. One chapter is written by Max where he describes the character of the Asmats, the feasts that different tribes celebrate, types of carvings, masks, spirits, customs, traditions and ceremonies, different types of wars, headhunting, initiation rituals for young men, rituals for the dead etc.

In 1999 when Indonesians attacked Timorese civilians after the referendum in East Timor, Max spoke to me on the phone genuinely distraught at the killings, stressing how it is a government’s duty to guide and protect its people. It is very unfortunate that Mr Hoffman’s book disparages a responsible and caring man who is no longer here to defend himself. Max and Etty are both long dead and had no children. So, there is no one to speak up for him. I have tried today, to speak up for Max Lapre. (Tamalia Alisjahbana)

If you enjoyed reading this article you may also enjoy by the same writer: